Crip Sweet Home

May 16th – June 29th 2024

Bradley Ertaskiran is pleased to present Crip Sweet Home, a solo exhibition by Canadian artist, performer, writer, and disability advocate Sharona Franklin. Set to the Bunker’s cold industrial backdrop, Franklin’s vivid mixed media artworks, imbued with poignant materiality and autobiographical details, chart individual and collective experiences of chronic illness, oscillating between comfort and discomfort. Throughout, Franklin beckons us in, then necessarily slams the viewer with potent inward questioning that confronts ingrained perceptions of disability and ableism: How do we project our feelings of disability onto others? And what is needed to properly understand it, to feel comfortable?

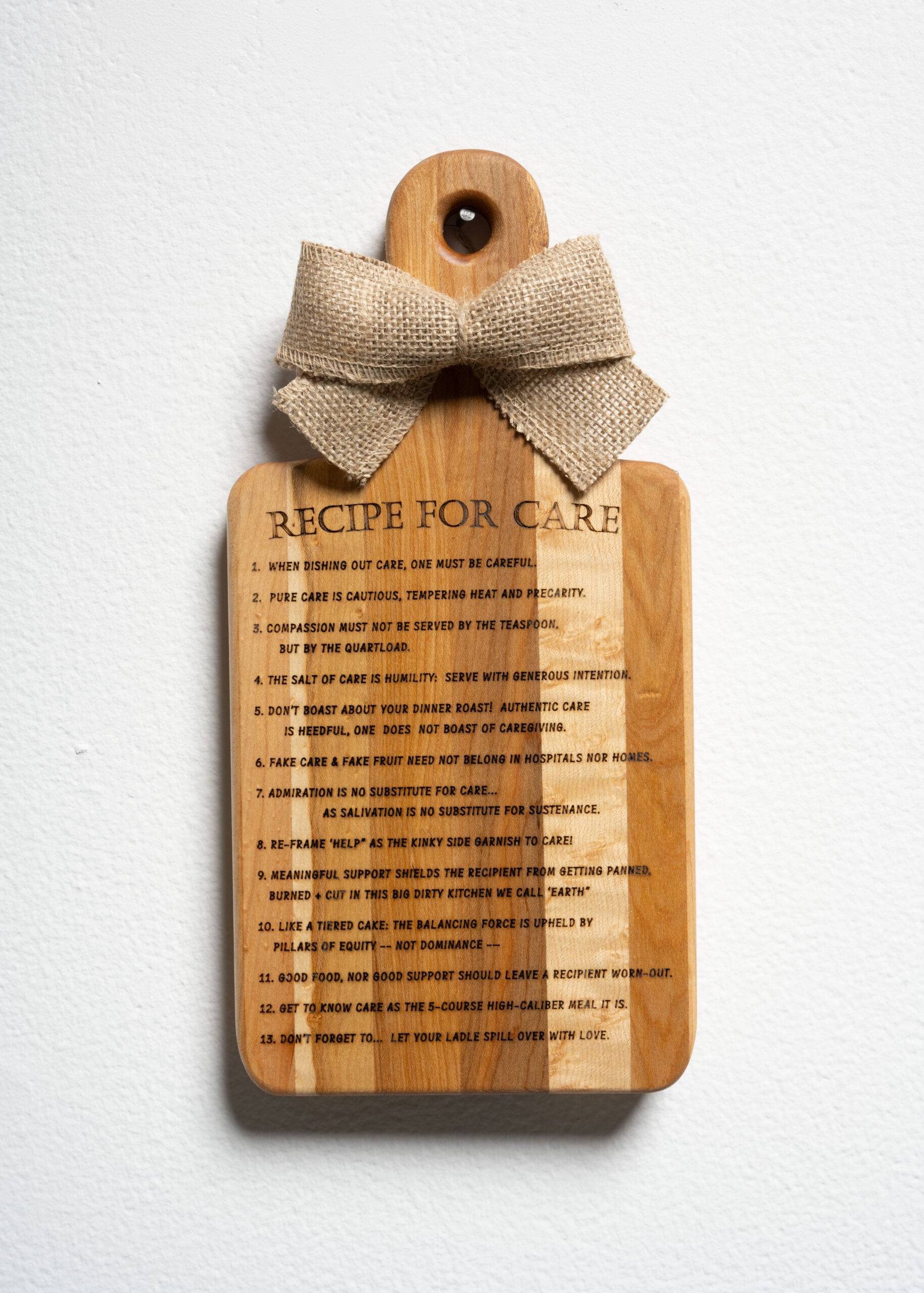

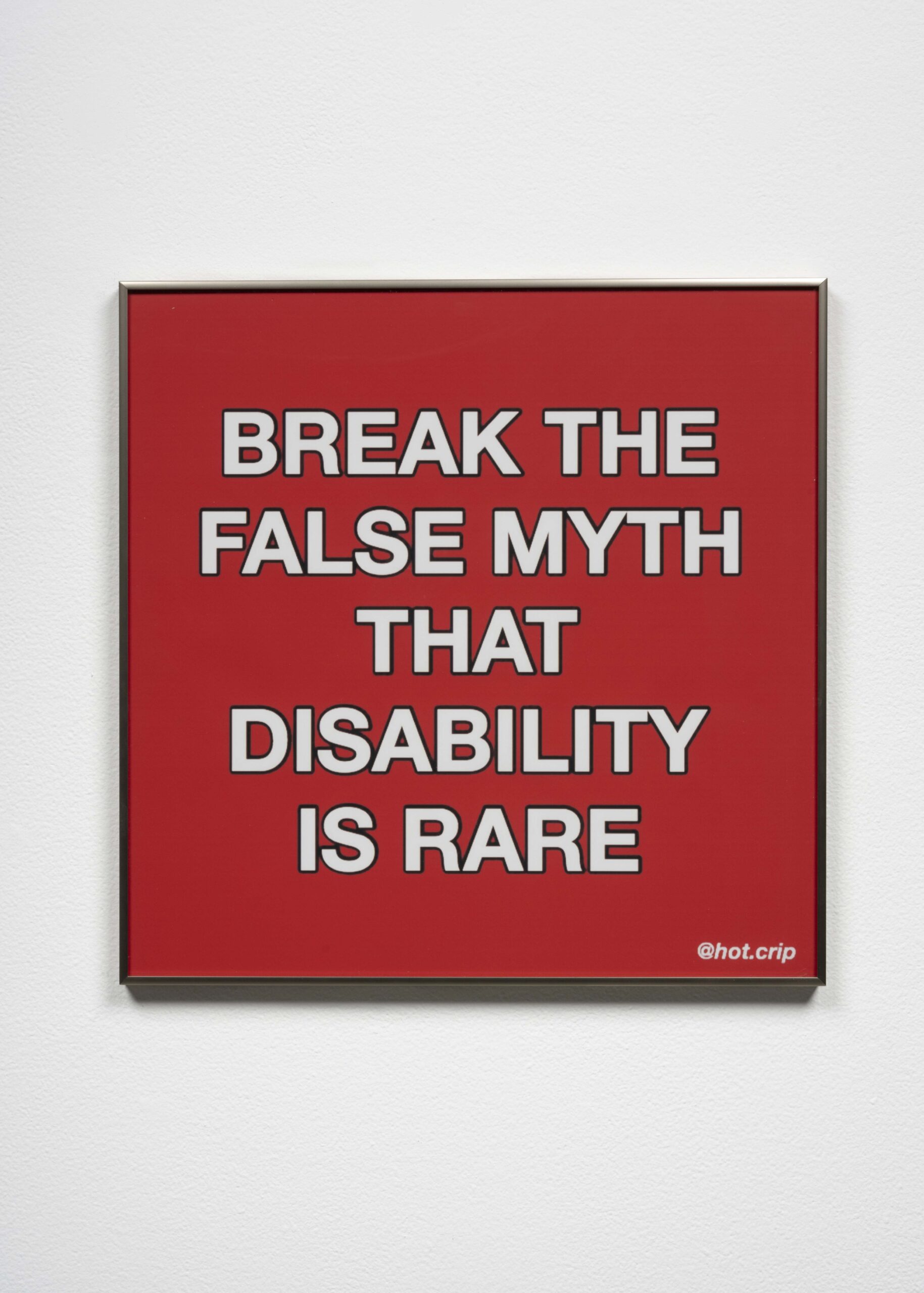

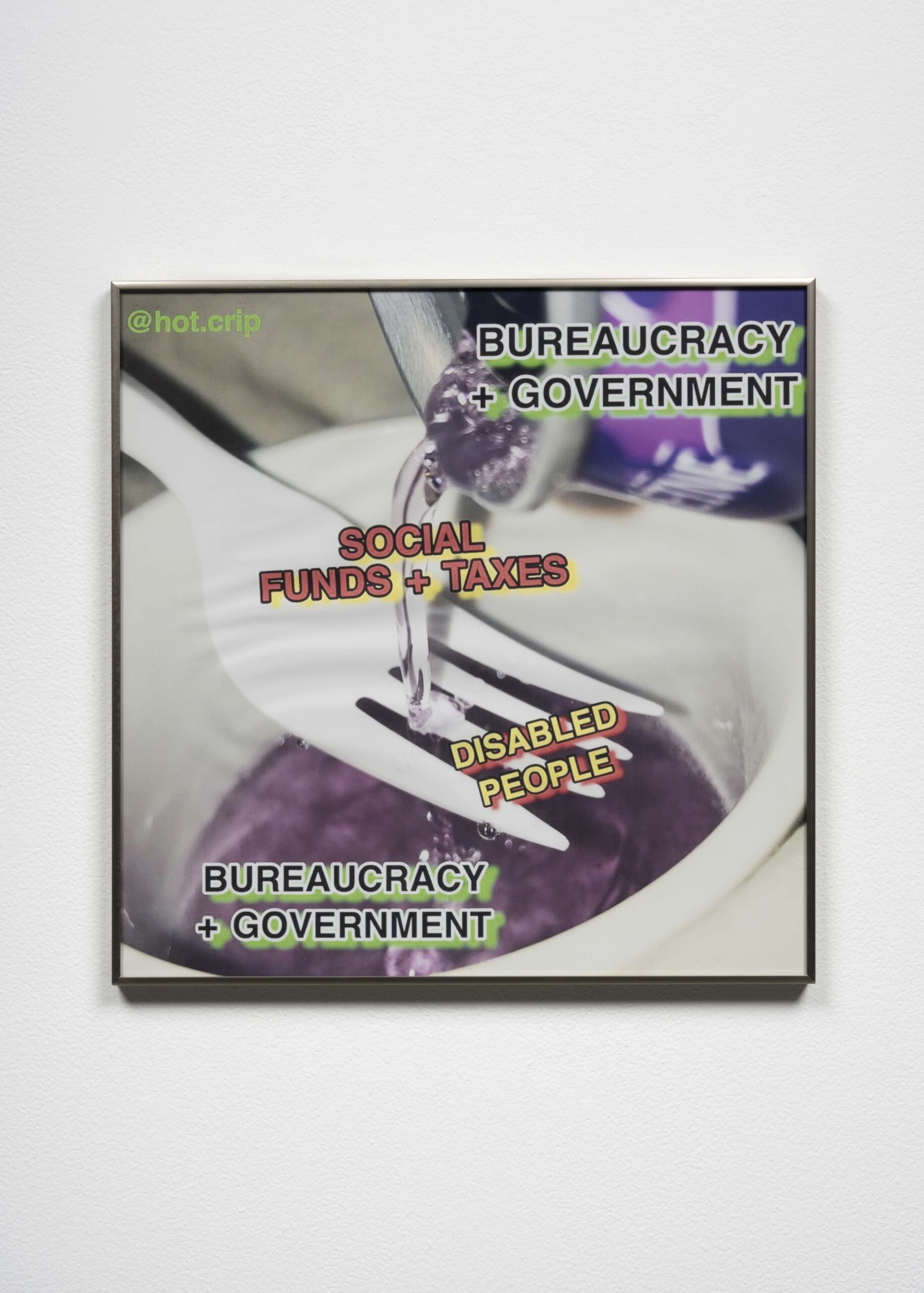

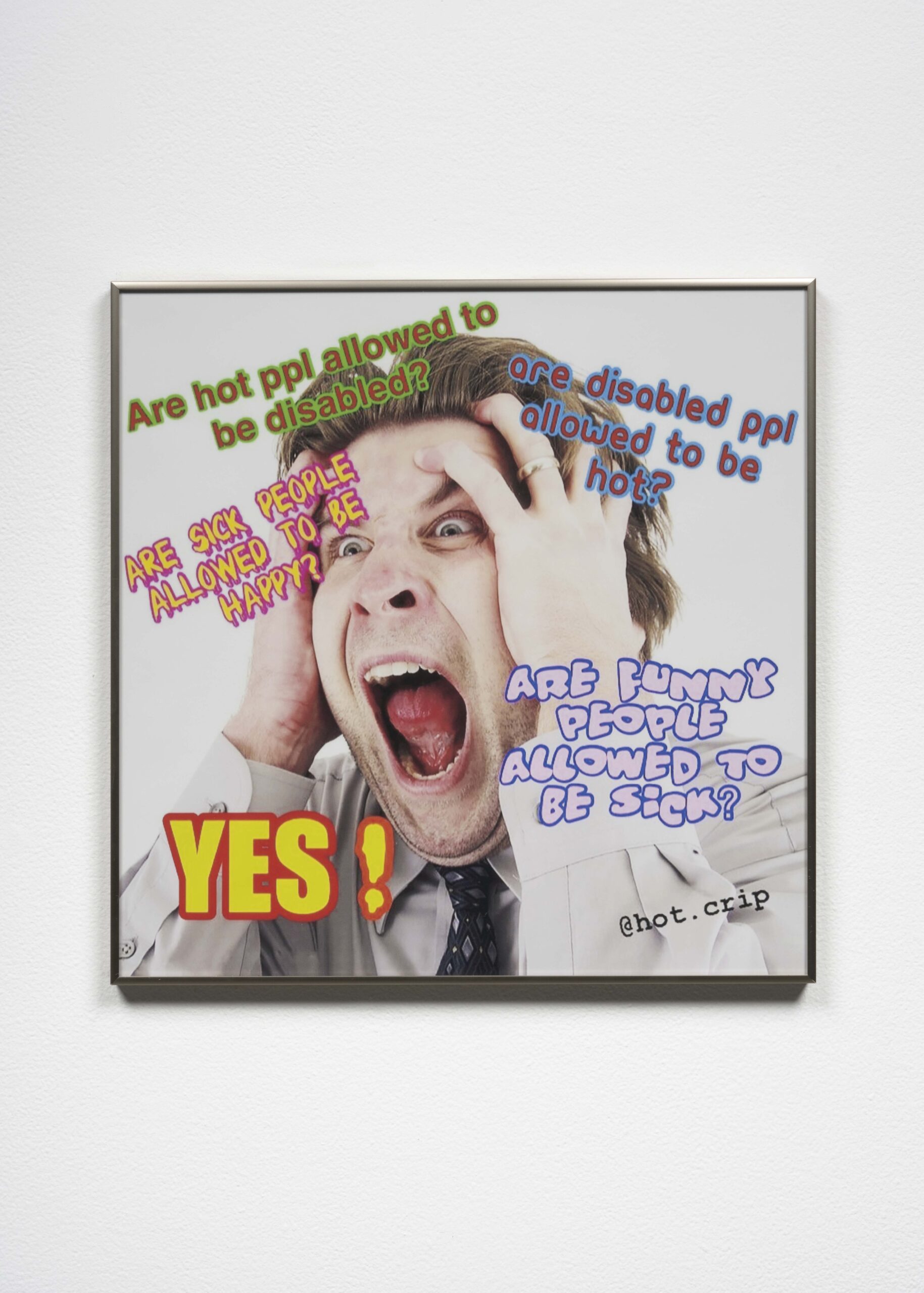

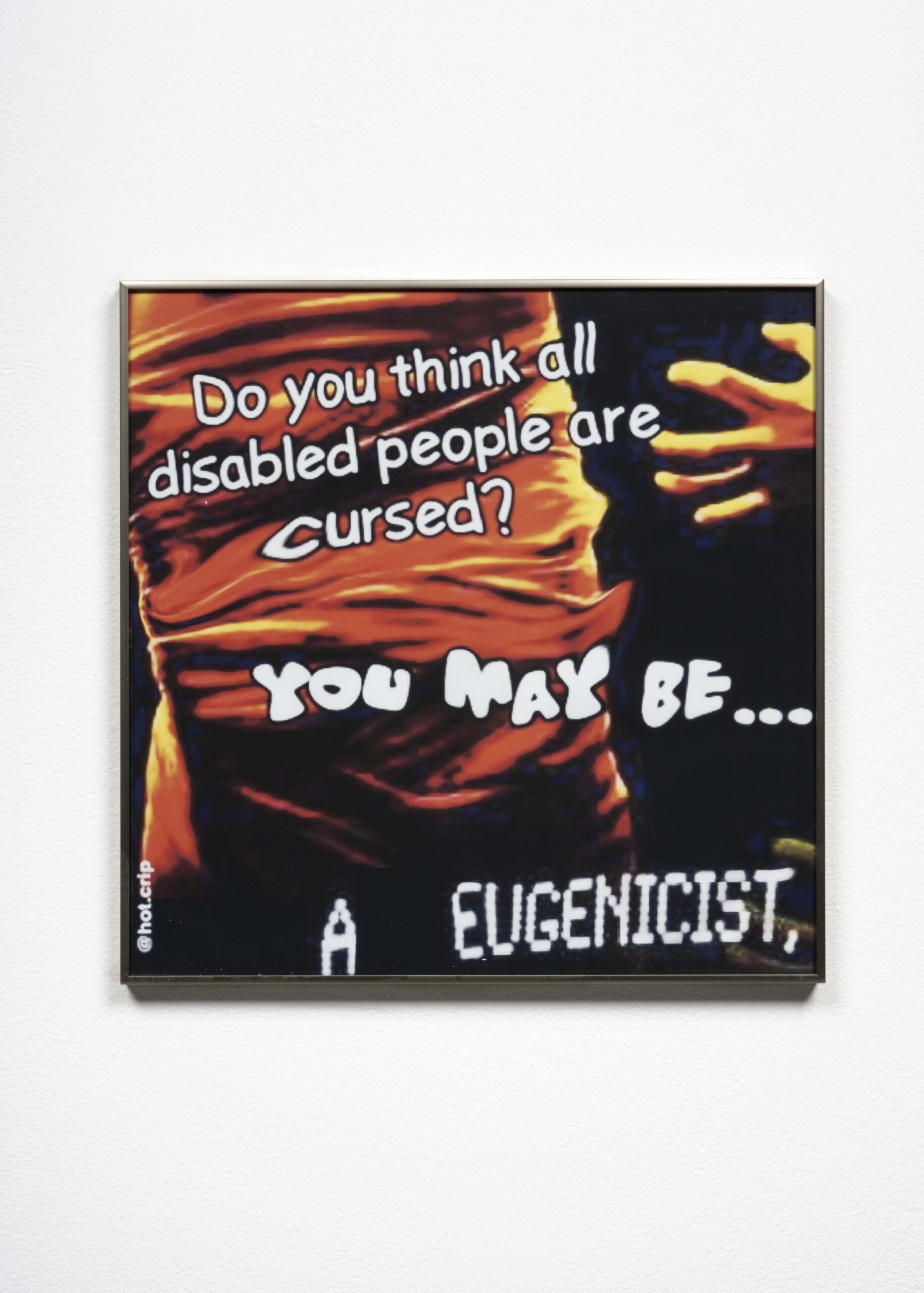

True to Franklin’s multidisciplinary practice, the exhibition comprises textile, sculptural, and written artworks, often borrowing from kitsch, digital, and domestic spheres, with provocative undertones. On the cement walls hang engraved black cast iron pans, wooden cutting boards, and needlepoint crocheted textiles, objects meant to welcome a guest into a home, here branding respective ironic care slogans laced with Franklin’s trademark wit. Framed memes hang nearby, no less bold and pointed, pulled from the artist’s ongoing online meme project, one of the first disability accounts on Instagram started in 2019, aimed at sharing comedy around ableism within everyday culture (@hot.crip). Franklin’s lyrical artworks employ critical humour as a form of advocacy and resilience, while acknowledging and resisting tropes of pity, worry, fear, or romanticization commonly ascribed to people with disabilities, ultimately turning the joke outwards towards the viewer.

Tactility is central to Franklin’s practice, exemplified in her expert assemblage of evocative materials into complex architectural installations. ‘The achilles of democracy is its dependence on popularity’ (2024), for example, comprises a staircase made of a molten chrome frame and yellowed steps of dehydrated gelatin. This structure is fatally engineered—the fragile staircase’s gelatin steps impossible to mount. Their design poignantly turns focus to the ailing body’s vulnerabilities and interdependencies navigating the structural and institutional barriers of daily life. Poetically detailed, the sculptures are ambitious and seductive yet distinctly repellent, a tactic that entices the viewer to inspect every element, every material, however uncomfortable. “Step a little closer,” they beckon, “look a little more carefully.”

A frequent character in Franklin’s practice, gelatin acts as a stand-in for the vulnerable human body: a lively, porous, but deteriorating thing. Franklin’s gelatin assemblages encase autobiographical materials—suspended syringes, pills, herbs, flowers, textiles, and hardware—a perfect mix of biological and medical-industrial matter, here moulded into fossil-like sculptures and stitched into a patch quilt. These sculptural collages illustrate personal experiences of illness, healing, and private life: colourful and soft overall, yet urgent in their emphasis on biomaterials, pills, and other life-saving goods. Medication is a recurrent symbol in Franklin’s practice, as a necessary self-sustaining resource, while also a potent reference to her tense relationship with bureaucracies and biopharmaceutical industries who manage and control disease. This fraught relationship extends to artworks like Hellraiser, a transformed infant’s cradle with overhead valance, and Alleles, a modified baby mobile, both carrying a palpable tension from the undercurrent of childhood pain, despite their usual soothing utilitarian function. Again, Franklin shows that when it comes to illness, comfort is an unlikely possibility.