Le Grand Corail

January 23rd – March 1st 2025

Text by Auttrianna Ward

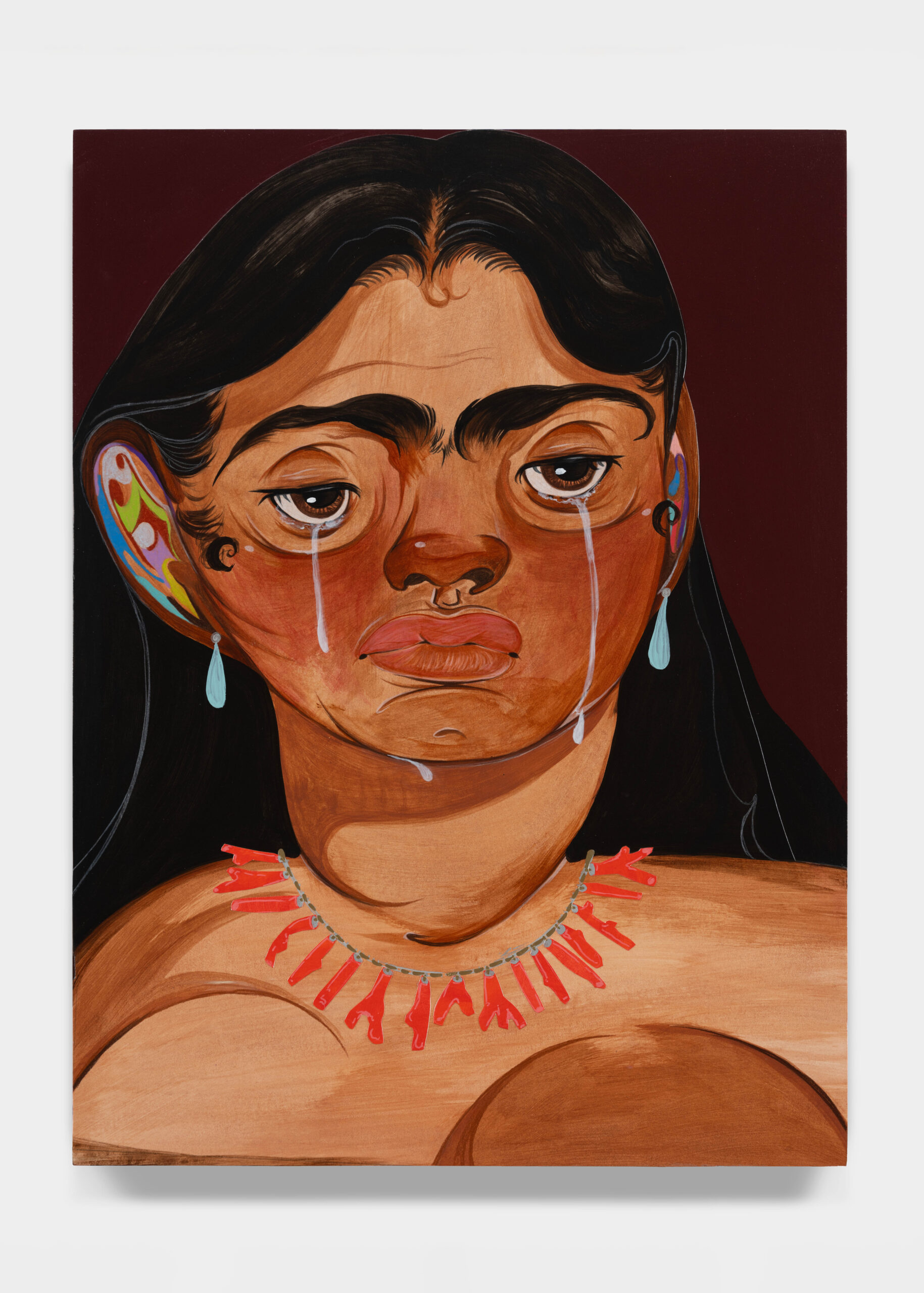

For when we speak of colonization, what happened to the body is also what happened to the land. The Caribbean, the original home of the Tainos, Arawaks, Caribs, Kalinagos, Ciguayos, and Macorixes, often becomes flattened through the tourist imagination—reduced to postcards and brochures selling paradise. This erasure silences the resilience, violence, and histories of these lands and their people. Bony Ramirez refuses this flattening. His work gives the Dominican Republic and the Caribbean at large incredible depth, complicating the outsider’s gaze while centering the narratives of Black and Brown bodies.

Hispaniola, the island now comprising Haiti and the Dominican Republic, was the first place in the Americas to receive African slaves. It was also the site of the first recorded slave revolt in 1521 at the plantation of Diego Colón, the son of Christopher Columbus. Later, Hispaniola became home to the most successful slave revolt in history, culminating in the Haitian Revolution and the formation of the first Black republic in 1804.

The fraught relationship between Haiti and the Dominican Republic serves as a complex historical backdrop, shaped by centuries of outsider colonial influences that imposed divisions and perpetuated cycles of violence in ideas and thought. These external forces—reinforced through exploitation, colorism, and political interference—fractured a shared history, leaving this tension embedded in the region’s collective memory.

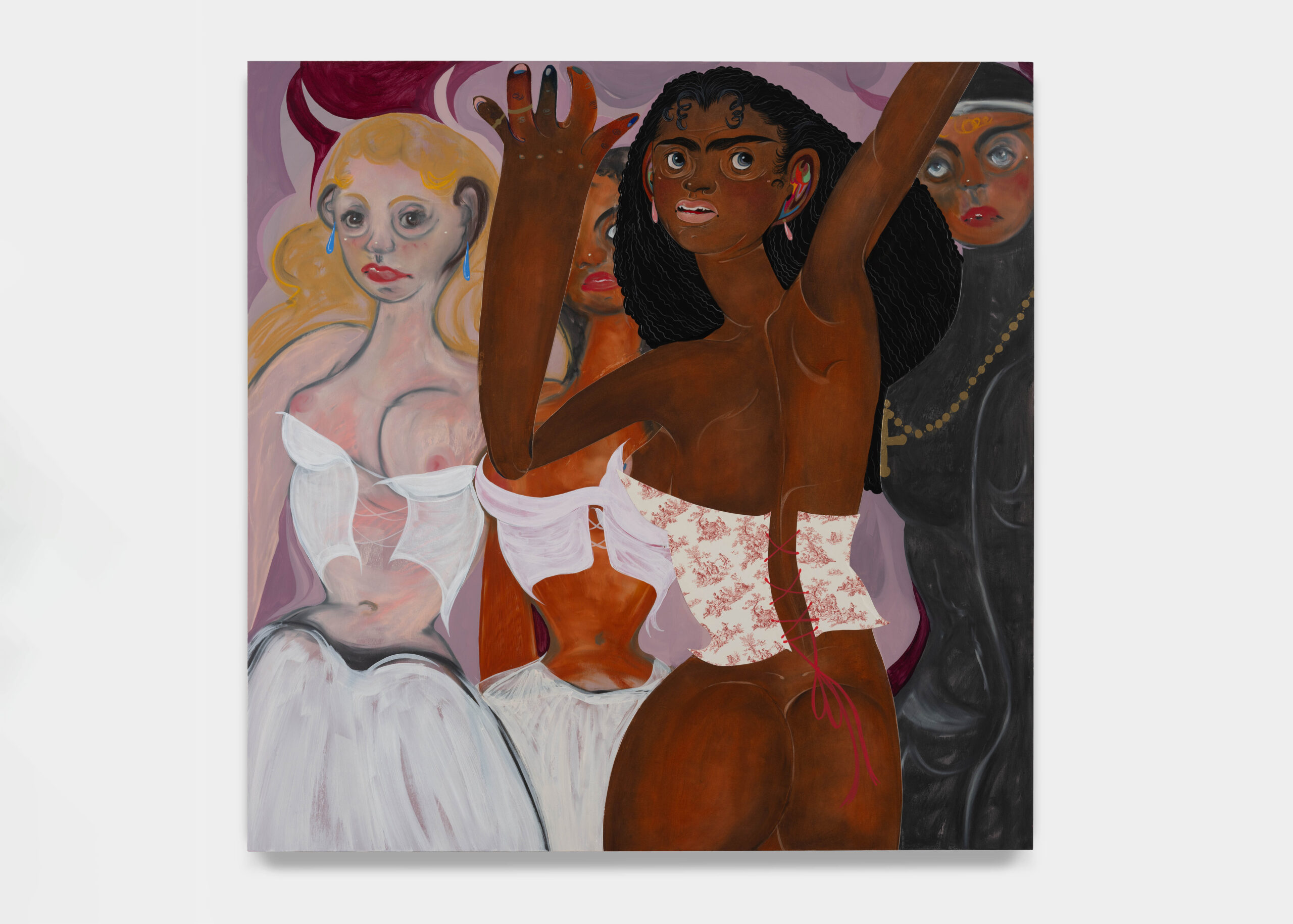

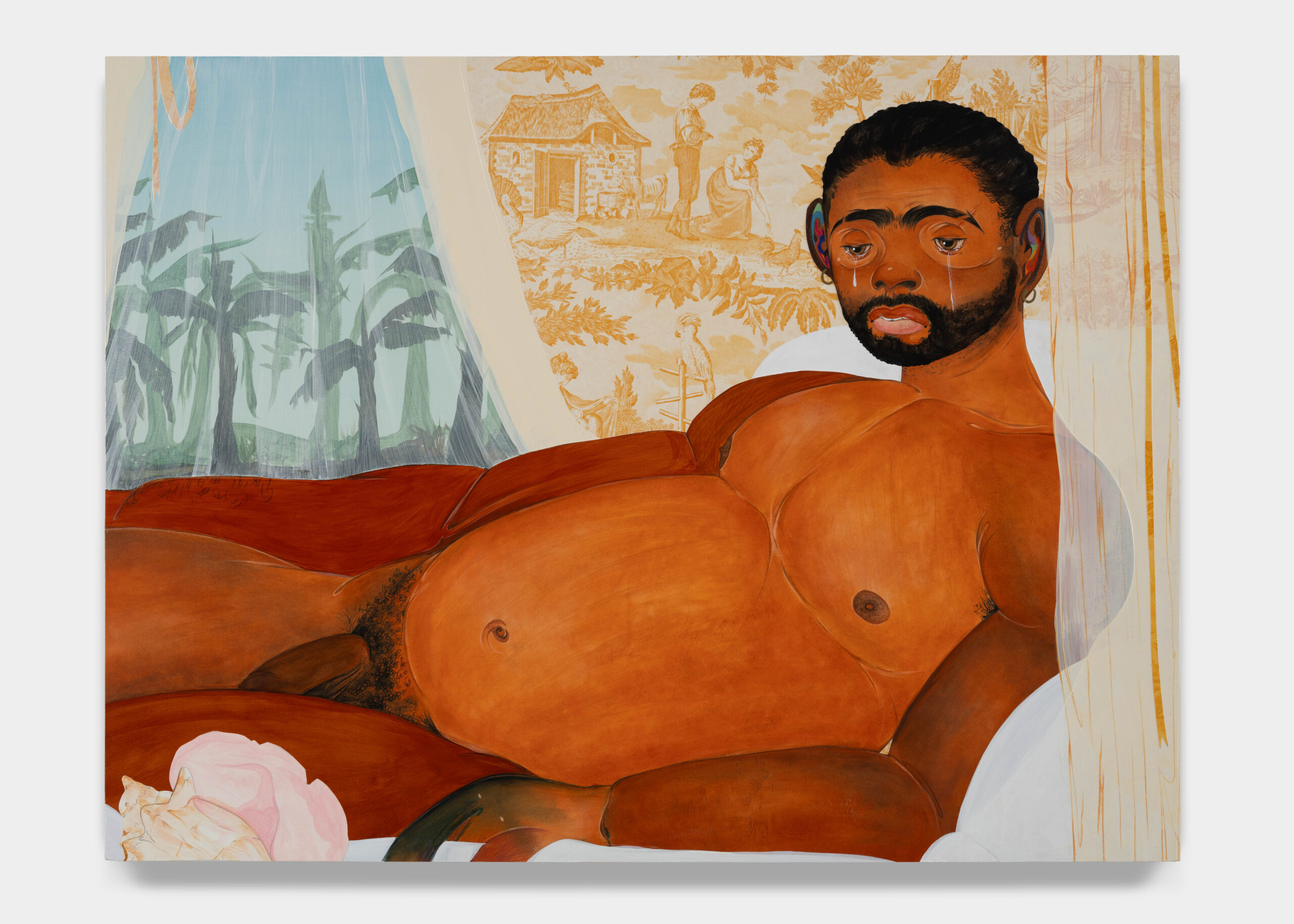

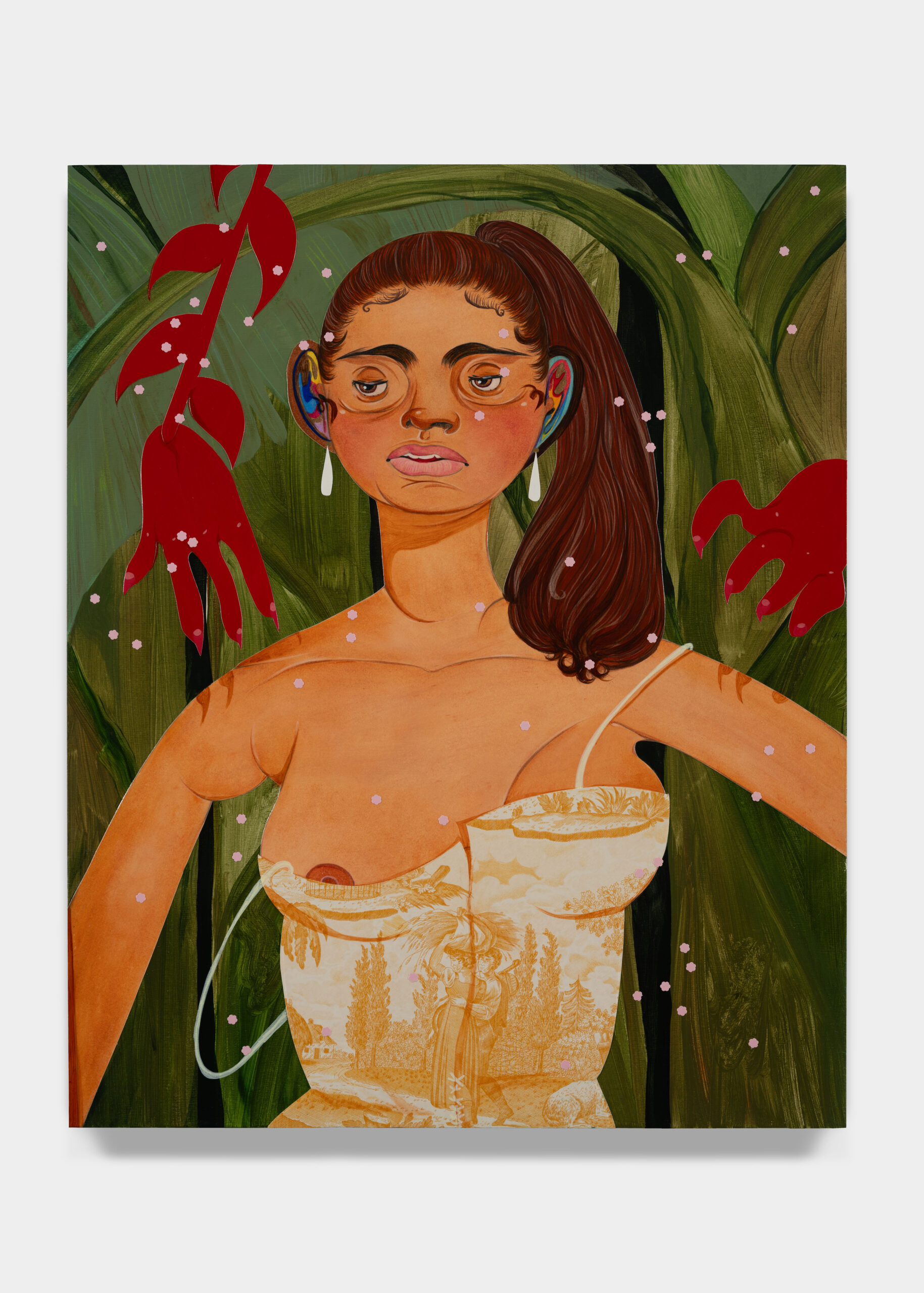

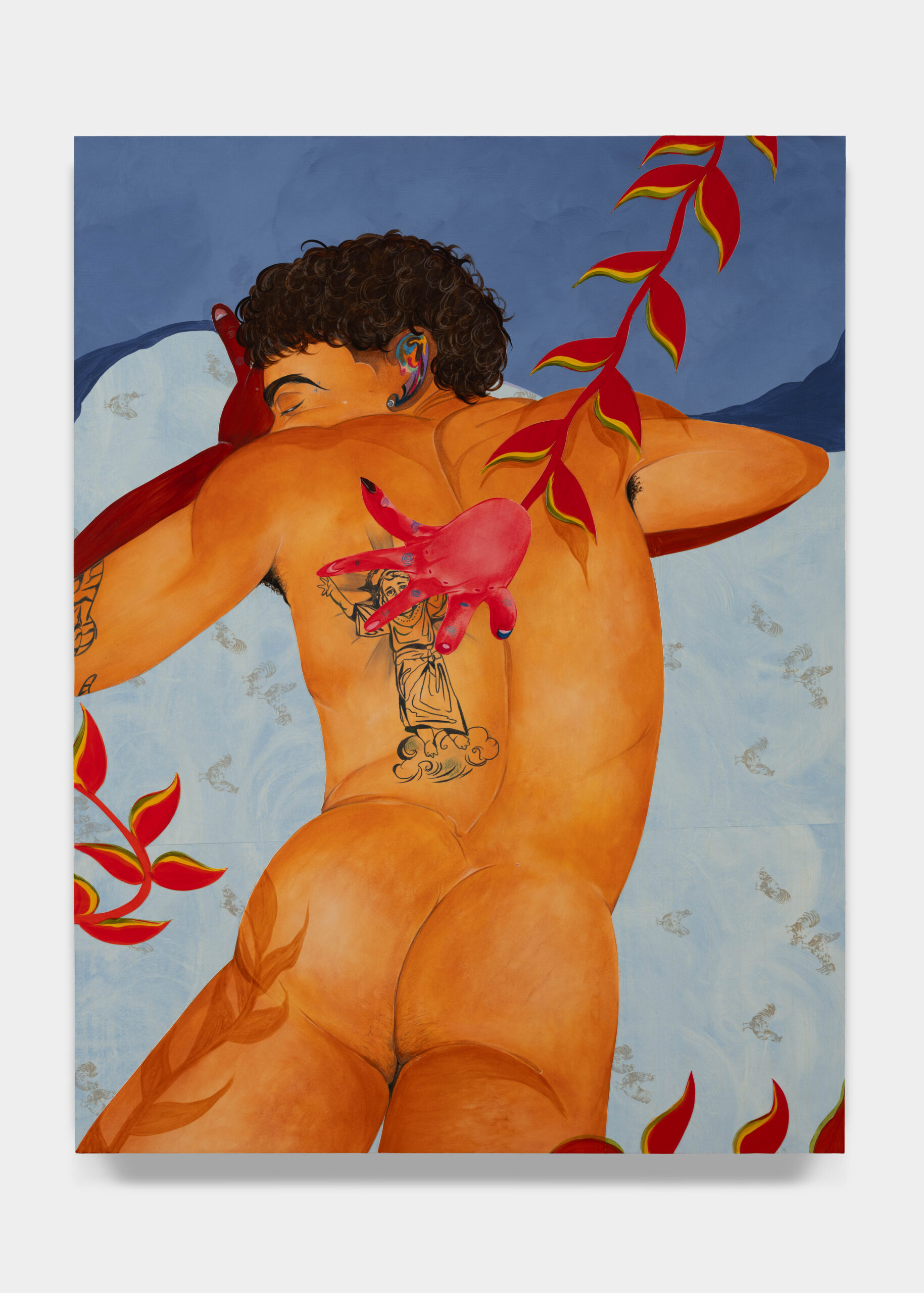

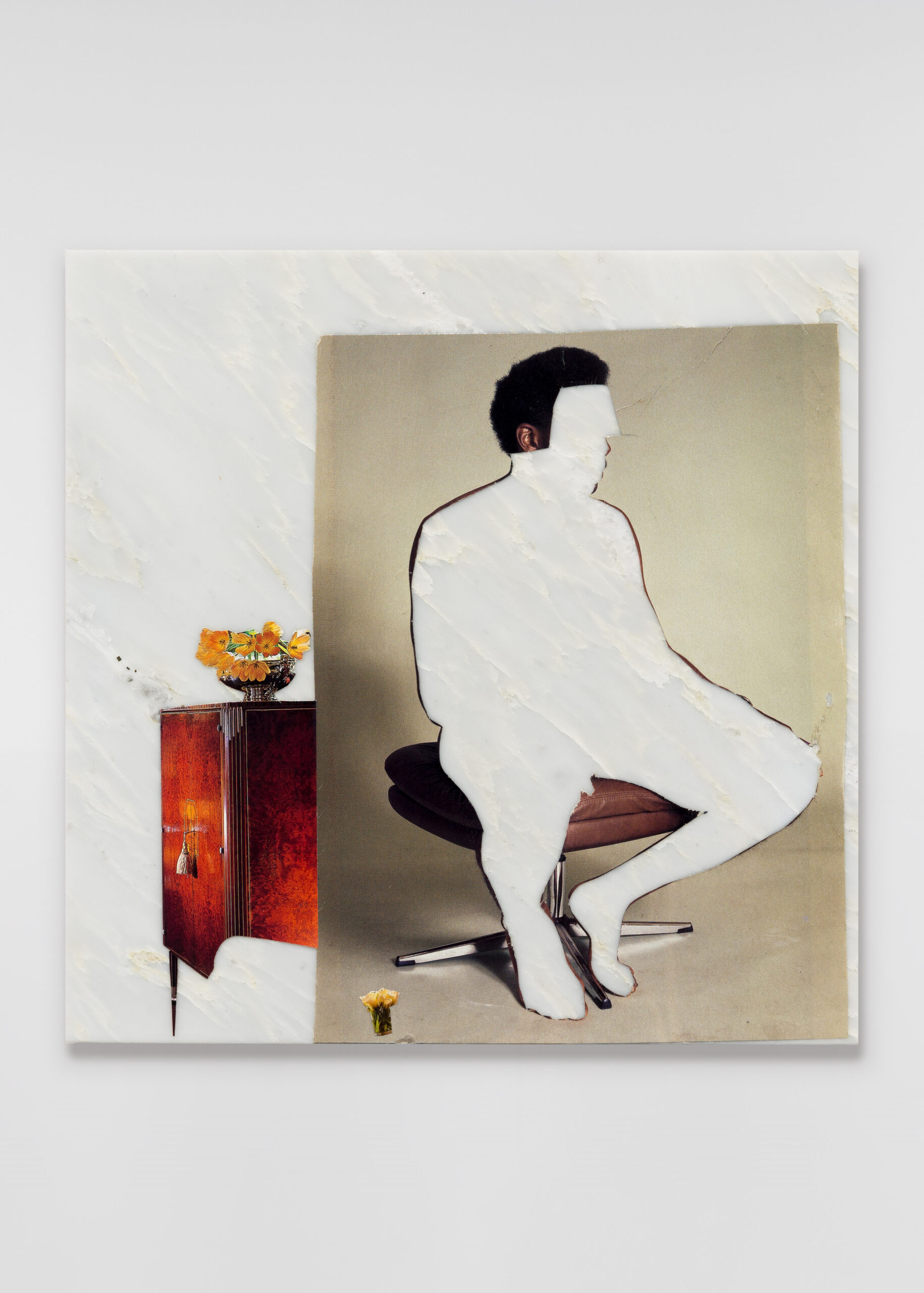

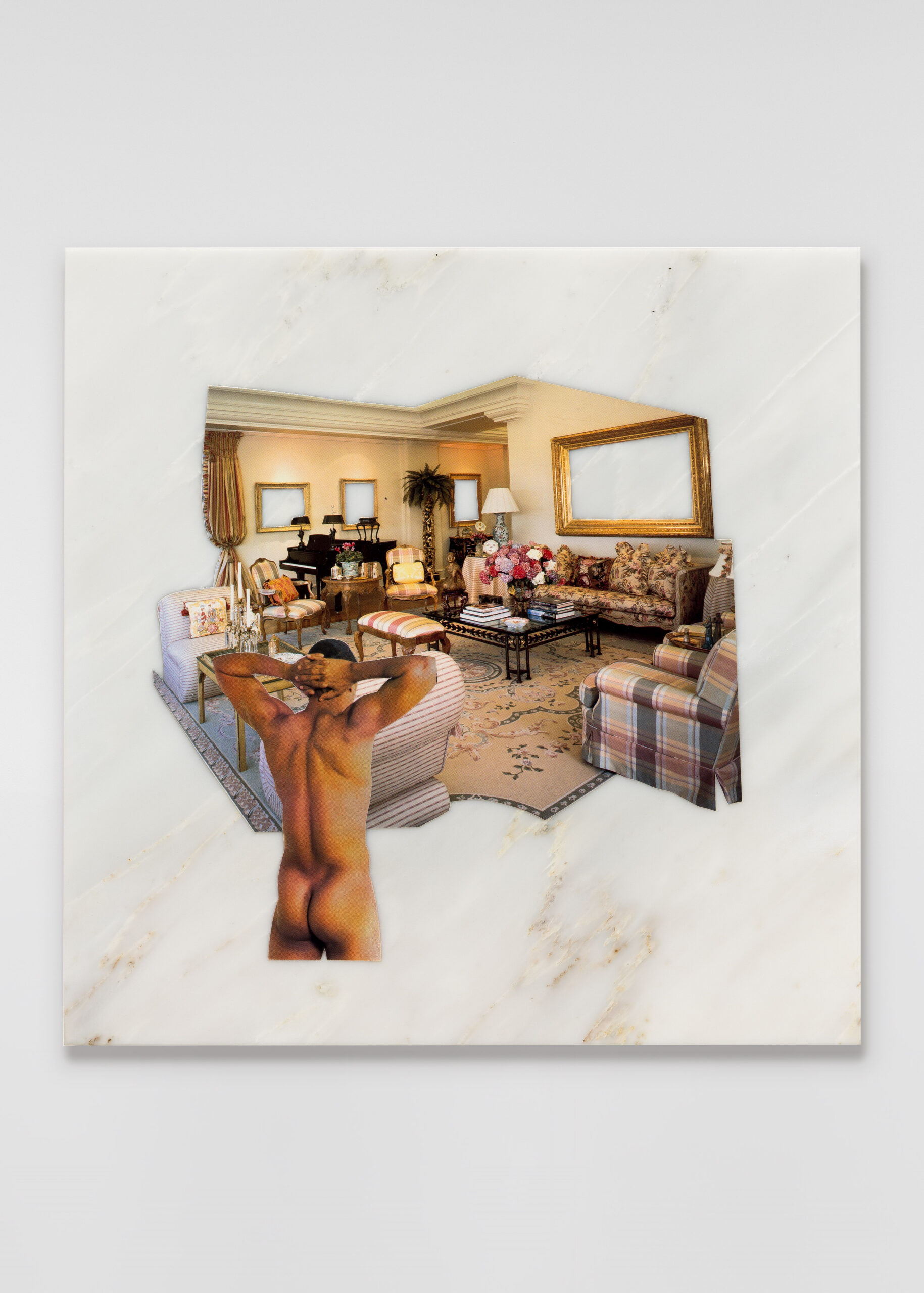

This island, as a birthplace of Blackness in the Americas, is central to Ramirez’s practice, grounding his work. His paintings, brimming with the oceanic blues, grand corals, and tropical greens of the Caribbean, explore the complexities of race, desire, and the commodification of Black and Brown bodies. By appropriating images directly from Tropic 2 Caribbean Colour Latin Spice & Black Heat, a gay adult magazine from 1985, Ramirez directly confronts the way colonization and sex intertwine in the outsider imagination of the Caribbean. These images—alongside sex tourism ads with language so overt it rivals Columbus’ diaries—are layered onto marble, a material that bridges his past as a construction worker with his present as a leading Caribbean artist dismantling exotified narratives.

The lustful tones of tourist ads, and even the way the art market itself exoticizes the very artists uplifting these narratives, linger in the background of Ramirez’s work. His painting In the Fight Between the Ring Ropes, 2024 subtly recalls the measurements of kidnapped Africans taken on the docks where they were sold, forcing us to consider how this history of commodification persists in contemporary portrayals of the Black body. His work creates a dialogue between the violence of history and the beauty of resilience, giving voice to queered and feminized perspectives that have long been ignored.

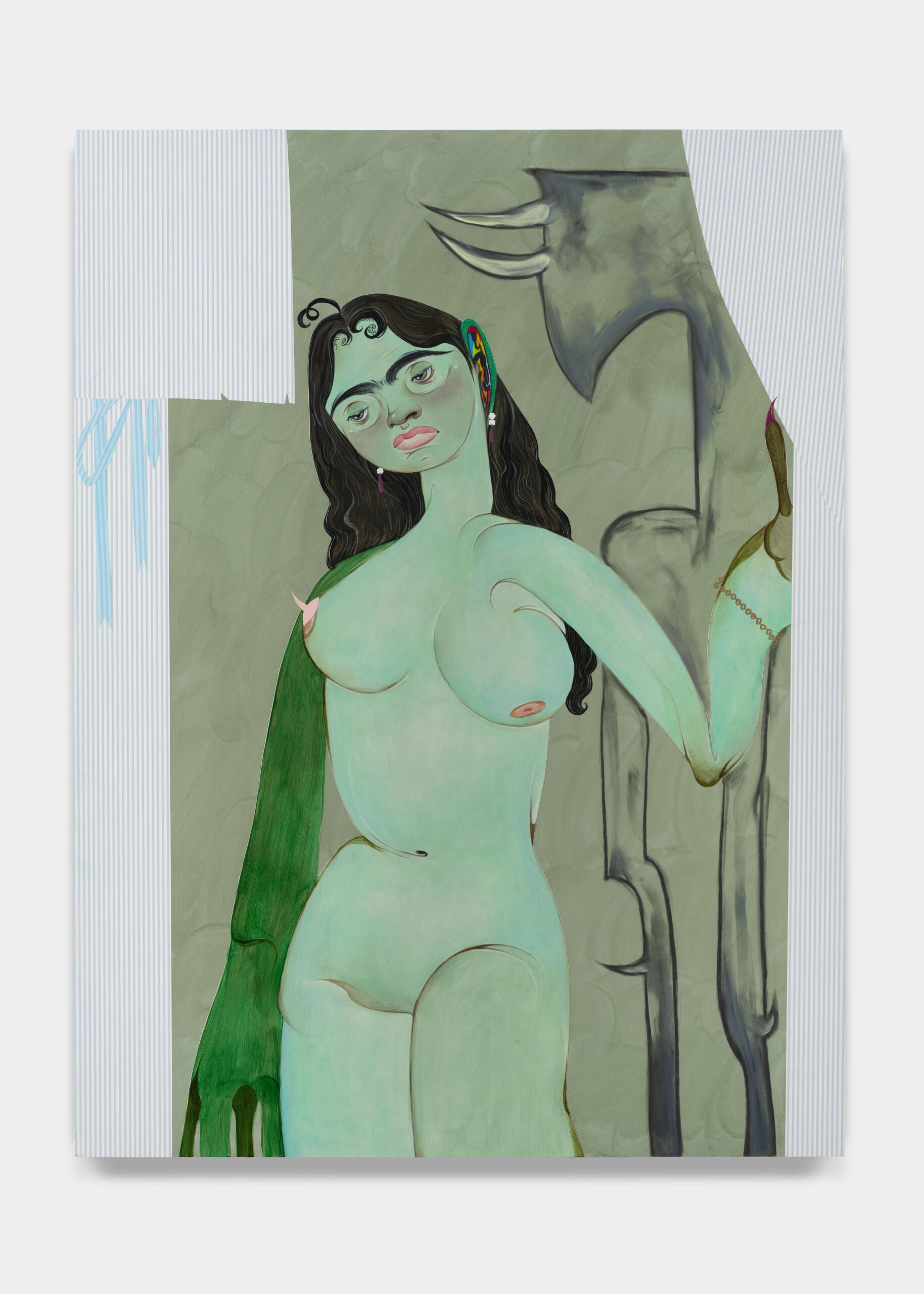

Ever the student, in Comienzo y Final de Una Verde Mañana, 2024, Ramirez dedicates the work to the memory of Afro-Cuban artist Wilfredo Lam, a legendary figure who brought global attention to the complexity and richness of Caribbean art. By referencing Lam, Ramirez not only acknowledges his place within this specific art history but also furthers it, shifting the axis by which these stories are told. His paintings create and uphold history while asserting that the Caribbean is not a site of erasure but of layered, living memory.

Ramirez’s practice, rooted in vibrant tones, religious iconography, and deeply personal materials, resists simplification. His work reminds us that the body, like the land, carries histories of violence and beauty, of resilience and exploitation. It demands we see the Caribbean not through the lens of an outsider but as a world alive with its own stories, voices, and truths.