Oasis

February 11th – March 13th 2021

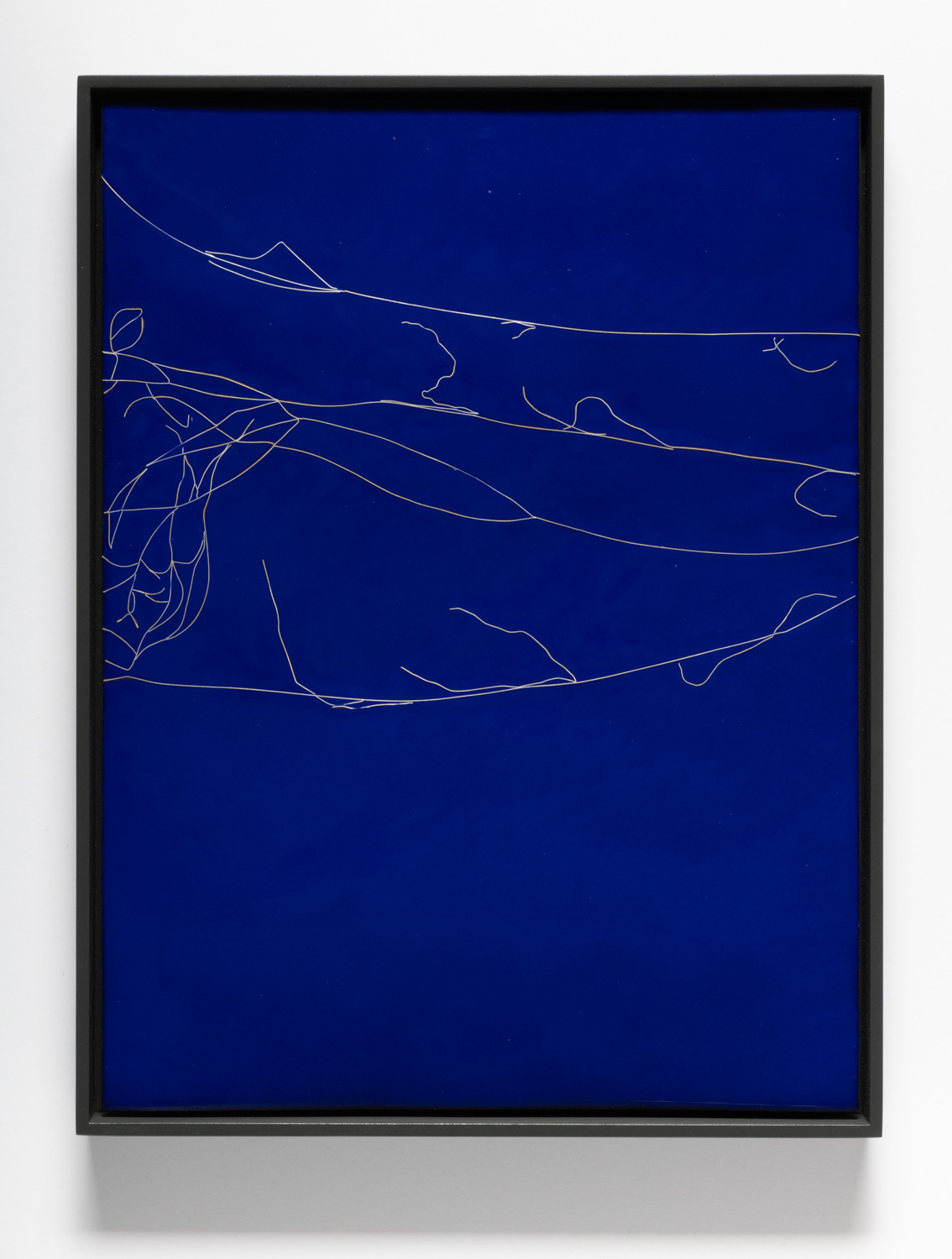

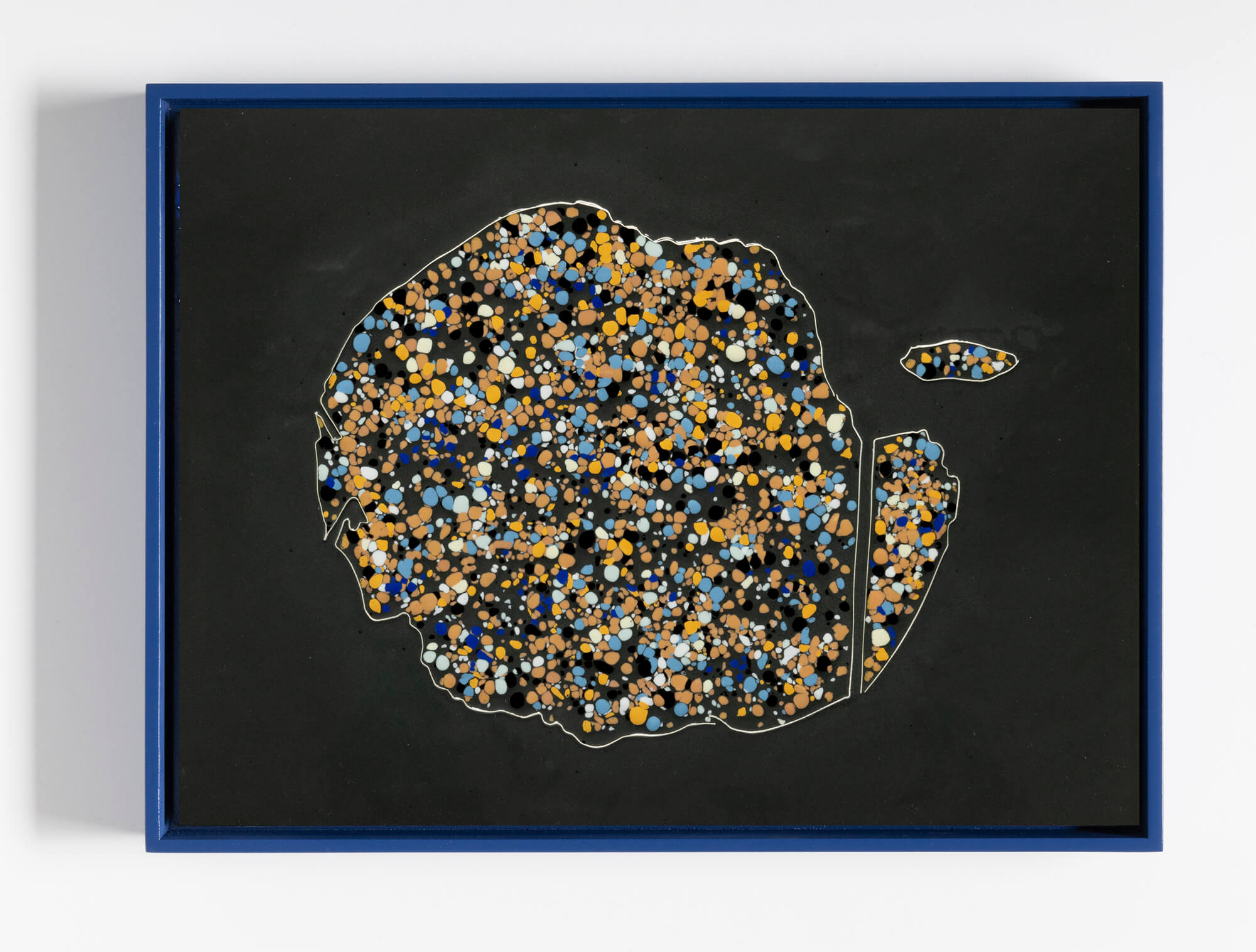

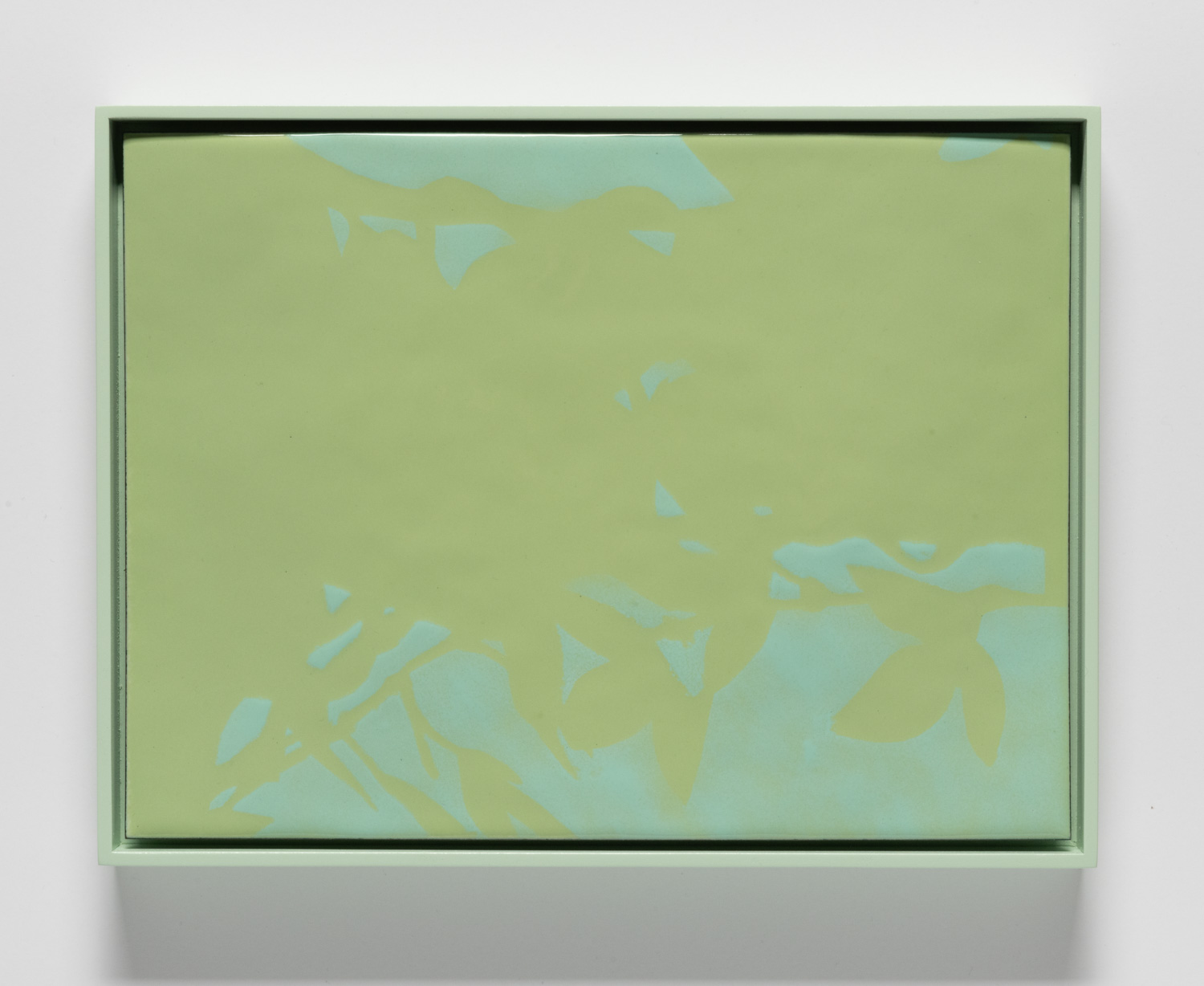

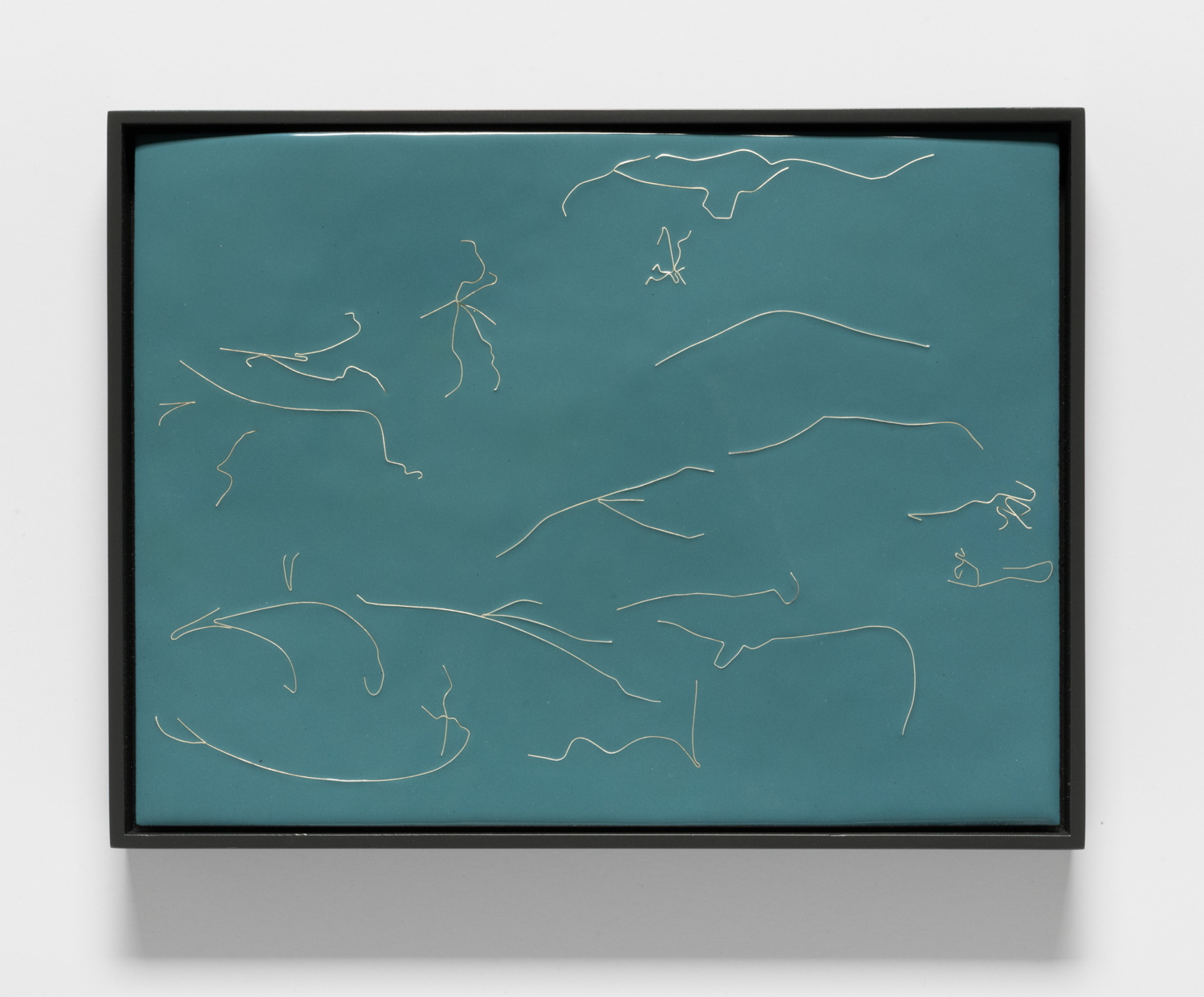

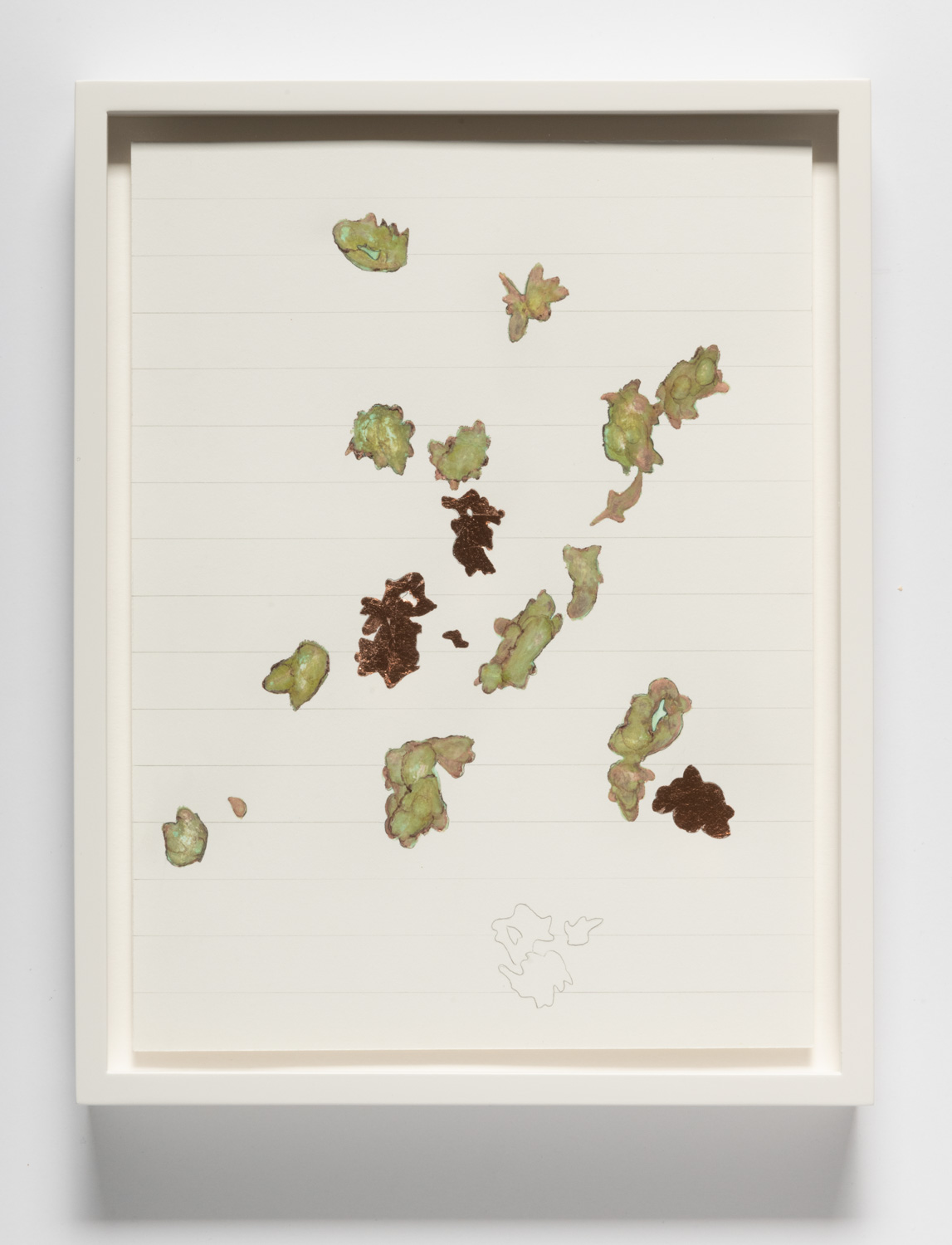

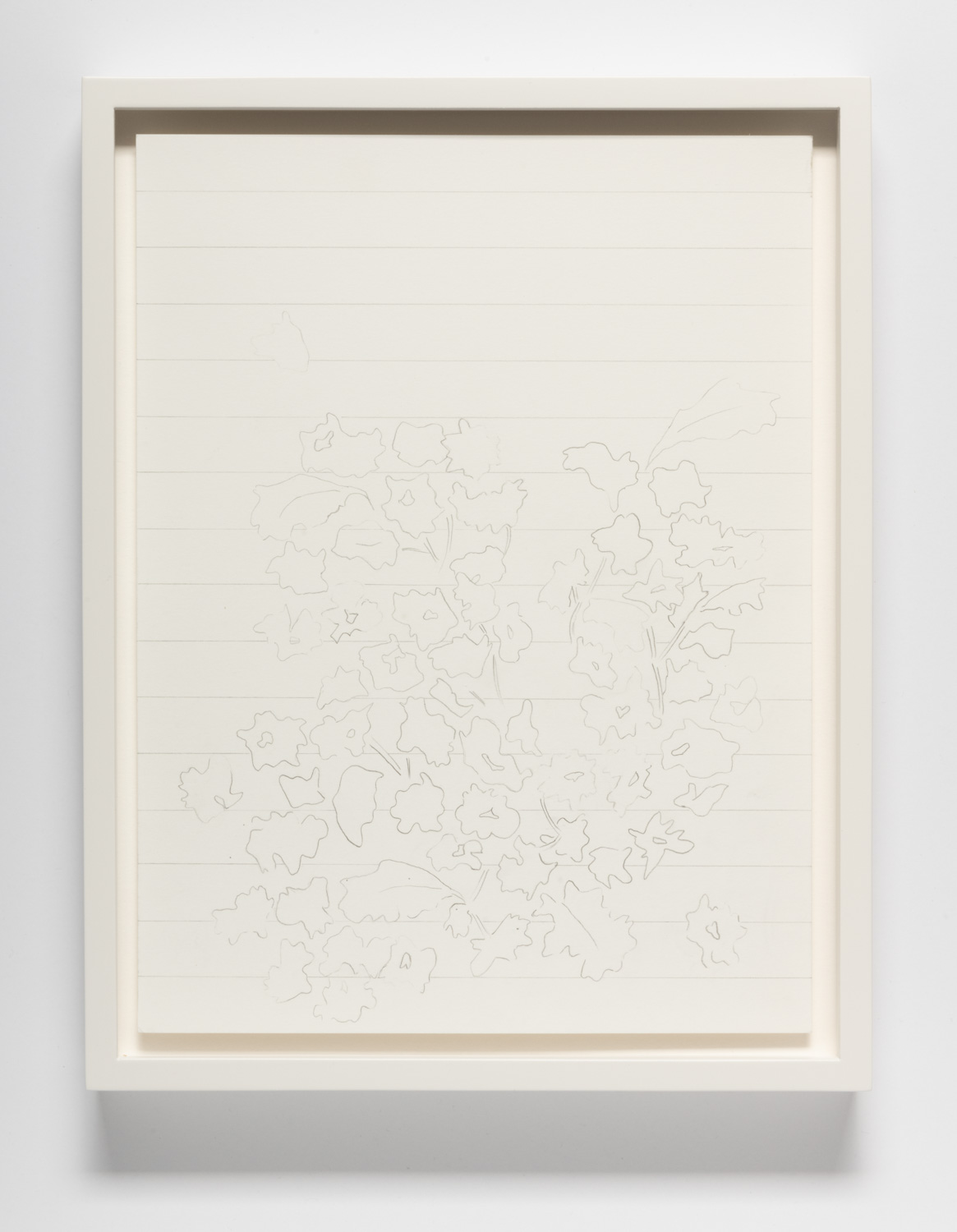

The body of work presented in Marie-Michelle Deschamp’s solo exhibition Oasis is inspired by the Voynich Manuscript, a 15th-century illustrated hand-written book, whose inscriptions have yet to be deciphered. Known today as possibly an early pharmacopeia, the Voynich Manuscript weaves an unreadable language with illustrations of botanicals. Mirroring this codex, Deschamps creates a biological language that is impenetrable. In her work, lines curve, repeat and roam, a labyrinth that cumulates and multiplies like an invasive vine is cemented in enamel—the practice itself an articulation of history. Interlaced with these silver lines, like graffiti inscribed into nature, Deschamps’s enamel paintings convey a universal statement, projecting themselves onto the future by way of the past. The layers of enamel echo the layers of time and history embedded in the soil of a garden. Gardens contain the past (seeds from hundreds of years ago), exist in the present, and will be propelled into the future as they continue to bloom. Art exists similarly.

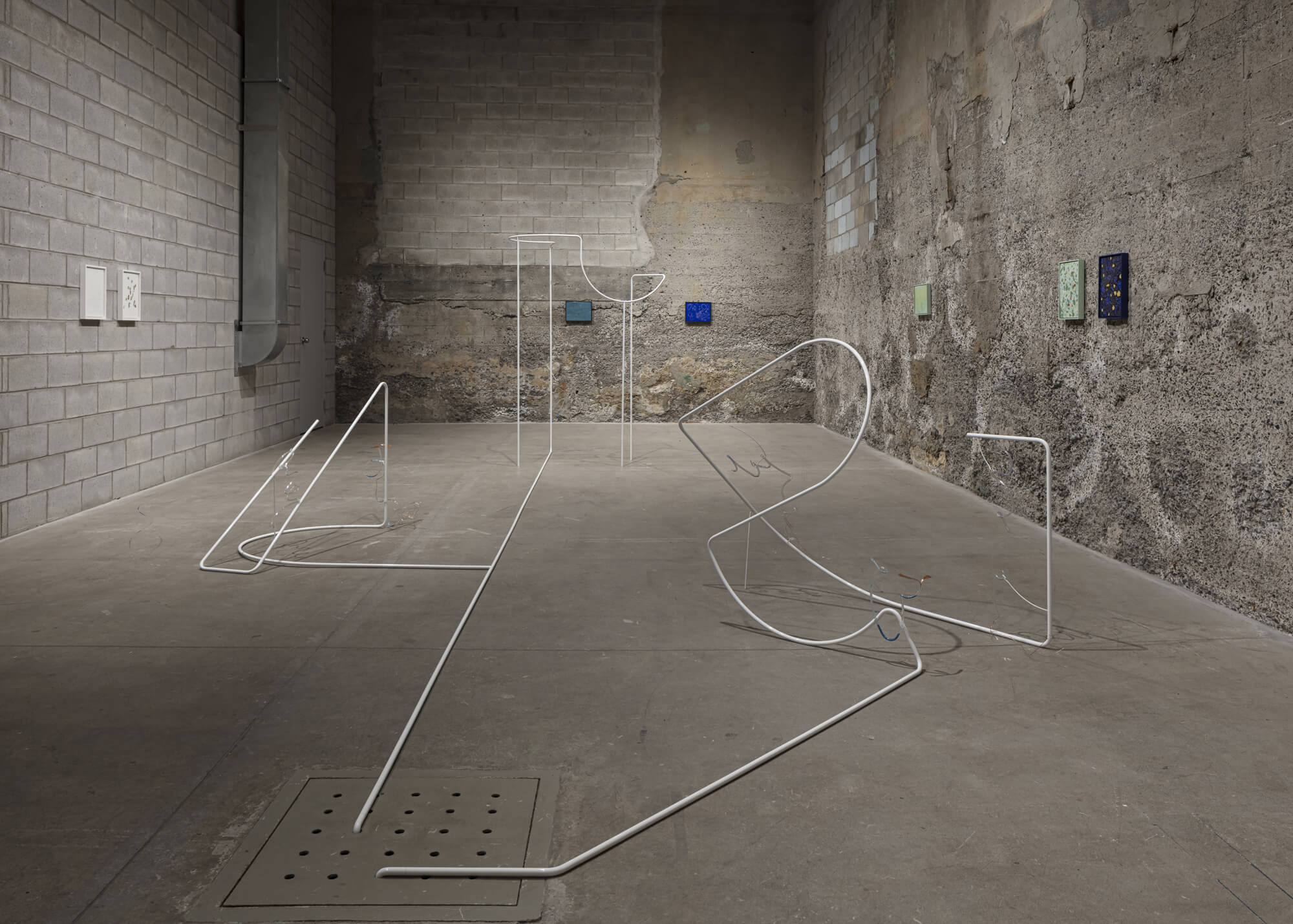

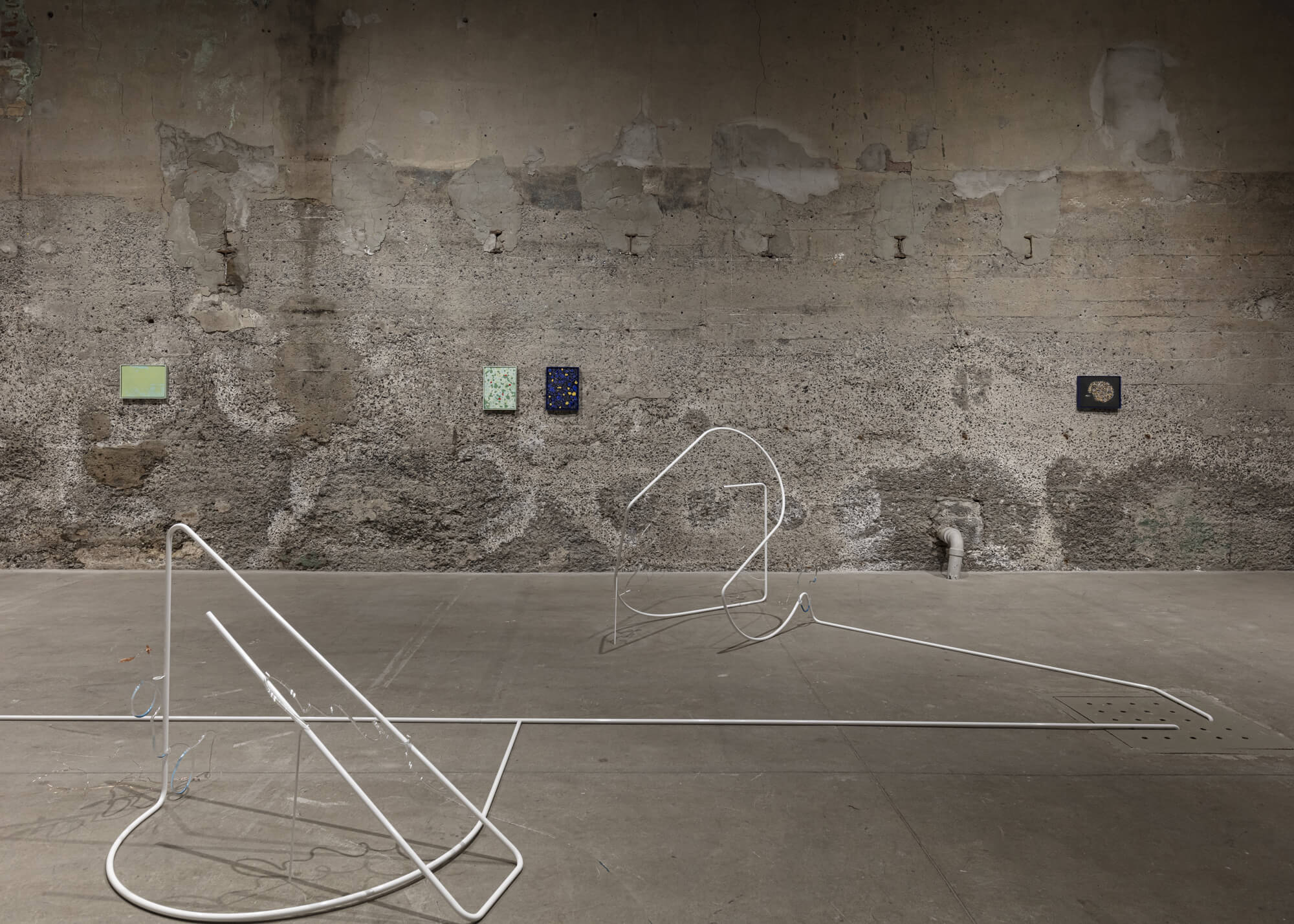

In my apartment, vines have overtaken my window, reflecting shadows on the walls which I follow as the day goes by. At night, the streetlights project the outlines of trees onto my ceiling, which I watch like a movie as I drift to sleep. The plants exist in two places at once, simultaneously outside and in. A shadow, like a mirror, reflects something real as unreal—ungraspable and slightly out of reach. The faint lines of a plant’s shadow remind me of Foucault’s theory of a heterotopia, a place that “is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place, several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible”[1], writes Foucault in his 1967 essay “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias”. Gardens, mirrors, hotels, and museums all exist within this definition. Deschamps’s sculptures and paintings can also be considered heterotopias, space where multiple meanings converge, creating something that is both knowable and unknowable.

“The traditional garden of the Persians was a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world” writes Foucault. “The garden is the smallest parcel of the world and then it is the totality of the world”[2] he continues. It was believed that all the garden’s vegetation came from its centre, where the fountain or basin was found. An umbilicus. Here, Deschamps’s sculptures fittingly emerge from the central drainage basin in the bunker space at Bradley Ertaskiran – a garden is sown.

– Tatum Dooley, January 2021

On the occasion of their simultaneous solo exhibitions Celia Perrin Sidarous and Marie-Michelle Deschamps have created several collaborative works that are installed throughout the gallery’s auxiliary spaces.

Marie-Michelle Deschamps holds an MFA in visual art from the Glasgow School of Art (Scotland). She has exhibited at the Darling Foundry (Montreal, Canada), Ausstellungraum Klingenthal in Basel (Switzerland), MUDAM (Luxembourg), Occidental Temporary in Paris (France) and Galerie de l’UQO (Gatineau, Canada). Deschamps’ work is found in the permanent collections of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal (Canada), Voorlinden Museum (Netherlands), the Lafayette Foundation Collection (France), the Glasgow School of the Arts Libraries (Scotland), and the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (Canada). Her work is also found in private collections in France, Canada, Italy, United Kingdom and Switzerland. She was longlisted for the Sobey Art Award in 2019, and is the recipient of the Sobey International Residencies Program at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York.

The artist would like to thank the Canada Council for the Arts for their financial support, as well as Aurélie Guillaume for her precious help to the project.

Bradley Ertaskiran acknowledges SODEC’s support in organizing this exhibition.

To consult the artist’s profile, please click here.

[1] Foucault, Michel. « Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias », written in French in 1967, published in Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, no 5 (1984): 46-49.

[2] Ibid.